BLACKOUT THEME

On the 1st September 1939, two days before the outbreak of war, Britain was blacked out. The Blackout imposed on all civilians in all cities was absolute. No chinks of light, no see through curtains, no car headlights. Even the red glow of a cigarette was banned. Britain was plunged into complete darkness.

Before the outbreak of war the Air Ministry had forecast that Britain would be exposed to sudden air attacks that would cause high civilian casualties and mass destruction from enemy night bombers.

To counter this threat it was widely agreed that if man-made lights on the ground could be put out then the enemy would find it difficult to navigate and pinpoint their targets. It was believed that if Blackout controls were introduced, it would make the enemy bombers job more difficult. Indeed as early as July 1939, Public Information Leaflet No 2 (issued as part of the Air Raid Patrol (A.R.P.) training literature) warned civilians that everybody would need to play their part and ensure that the Blackout regulations were properly enforced during the Blackout periods.

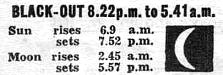

PICTURE: Blackout times for today are..........

The Government ensured that there was enough Blackout material for each household. Blackout material had to be readily available but cheap enough even for the poorest families. In most cases black cotton fabric was used meaning that the bigger the house you had the more you had to pay for your windows to be covered. That is all except the local vicar who was given a certain amount of sympathy when asked to Blackout his vicarage.

Putting up Blackout material proved more time consuming than was first imagined and quickly became a tedious chore for most families.

Families could spend a long time putting up the Blackout materials only to find that one thickness of fabric was not enough to stop light from escaping and drawing the attention of a A.R.P. warden or eagle eyed neighbour. Indeed two or three thicknesses was often required before all light was snuffed out. Even pinning these sheets to window frames could prove troublesome. Householders were lucky if they had wooden frames but many had stone or metal frames proving that hanging this fabric could be an achievement in itself. Some tried to save time by lining their windows with black paper and pins. This was fine initially but with the continuous taking down and putting back up this method didn't last long!

With the introduction of the Blackout came stringent regulations and harsh punishment for people that did not adhere to these rules. The local A.R.P. could report anyone to the local authorities if any sign of a light was seen. Many householders would sit and wait for that knock on the door to tell them they had a chink of light shining from their homes. Being reported could lead to a hefty fine or in some cases an appearance in court.

Businesses faced even greater difficulties with the introduction of the Blackout. Many factories had glass roofs which had to be painted black meaning that workers had to work day and night under the glare of artificial lights. This proved difficult for workers by affecting their morale and expensive for their employers.

Local shopkeepers didn't fair much better either. As well as darkening their windows they had the added dilemma of how customers could leave their shops without any light escaping. The solution meant a double door much like a photographer's dark room where people would open one door and shut it behind them before opening the main shop door.

Total darkness was exciting for some because it meant their first glimpse of the night sky with no reflection of city lights. However for most trying to get around was confusing, frightening and dangerous. Road accidents were on the increase and drownings also rose dramatically where people fell off bridges and into rivers or into ponds.

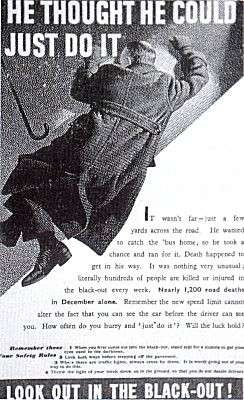

As can be seen from the newspaper clipping on this page (see below) fatalities and serious injuries were a reality of the Blackout.

PICTURE: Press article from the Daily Sketch

PICTURE: Press article from the Daily Sketch warning people to be careful in the Blackout

People complained bitterly that the Blackout saw crime rocket, particularly petty crime such as pick pocketing and the raiding of vegetable patches (see our page on Dig For Victory). Crime did increase but not as much as people exaggerated. The simple fact is that petty criminals could never be sure if people were at home or not during the Blackout and often thought it better not to take the chance of breaking into houses in case they came face to face with the householder!

A jingle around at the beginning of Blackout restrictions entitled Billy Brown's own highway code seemed to say it all. The fact that authorities endorsed this jingle indicated a softening of stance as well. Before mid October 1939 no torches were allowed at all but now they seemed to be permitted.

By the New Year it was widely agreed by the authorities that restrictions needed to be lifted to try and alleviate the numbers of pedestrian accidents. One measure was the issuing of a small pocket torch (the No. 8). However No. 8 batteries for these torches were scarce and most people continued to wander aimlessly in the dark.

PICTURE: Poster reminding pedestrians not to flag a bus with their torch

If you were lucky enough to have batteries it was necessary to place tissue paper over the main beam of the torch and point it downwards. The torches could be used to hail a bus during the Blackout but the Ministry of Information stated that the following must be adhered to.

Due to the high road casualties in 1940 the speed limit for motorists was reduced to 20 mph during the Blackout. Central white lines were painted in the middle of roads (which are still with us today) and curb edges were painted white as well. Kerb finders could also be used which were attached to a walking stick or umbrella.

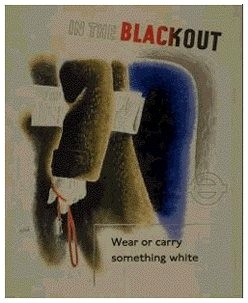

Pedestrians were reminded also that they should always walk facing the traffic and that they should carry or wear something white. Armbands were also worn that were luminous in the dark. These were exposed to the daylight to absorb light and emitted light in darkness.

PICTURE: 'He thought he could do it!' Poster reminding motorists to adhere to the new speed limit

PICTURE: 'Wear or carry something white' poster

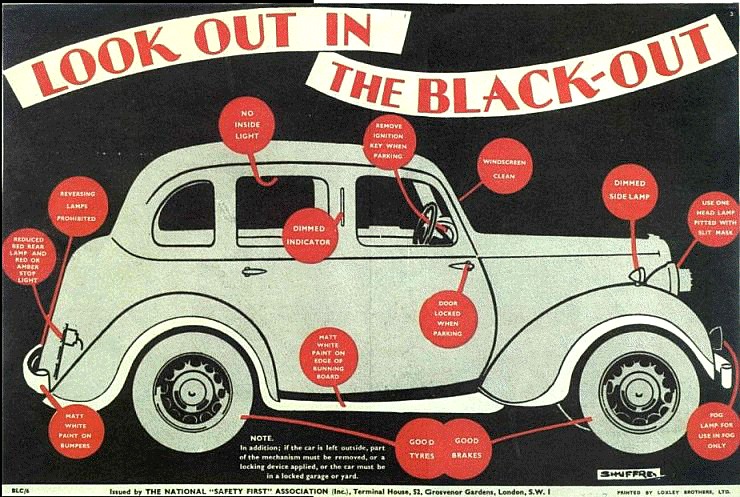

PICTURE: Poster advising motorists of how they should prepare and use their car in the Blackout

The following poster reminded motorists of how they should prepare and use their car in the Blackout. It told them that they should display no interior lights and use a slit mask (comprising of 3 horizontal slits) for the headlamp, an ingenious invention introduced in 1940. Indicators had to be dimmed and the red rear lamp also had to be reduced. In reality lights were so dim and pointed downwards that most motorists could not see the signs as to where they were going. Eventually due to this and also petrol rationing fewer and fewer cars were seen on the road during World War Two.

There were a great deal of posters during the war reminding people to be careful during the Blackout. The following gives a few examples of posters you may have seen at this time.

PICTURE: Poster reminding people to count and wait before moving in the Blackout

PICTURE: Carrots were one vegetable in plentiful supply and as a result widely utilised as a substitute for the more scarce commodities Here people are reminded that carrots can also help you to see better in the dark. See our page on Dig For Victory

PICTURE: Another poster reminding pedestrians to look out in the Blackout

PICTURE: A comic view of how the Blackout could have its advantages!

Despite the strict Blackout regulations enforced on a tired Britain, Britons did not lose their spirit as the following comic strip proved in the darker days of World War Two.

The Dim-out was introduced in September 1944 and meant that lighting the equivalent of moonlight could at long last be introduced. However the authorities still insisted that a full Blackout should be imposed if an alert was sounded. People all over the country breathed a sigh of relief. The Blackout was a restriction imposed on ordinary people that was both unpopular and often resented because of the time it wasted. Full lighting of streets that had not been seen since before the war eventually came in April 1945. Symbolically for Londoners it was the illumination of Big Ben that ended the Blackout in London. This came on the 30th April 1945, 5 years and 123 days to the day of when the Blackout descended on Britain.